"While looking for academic (mostly, but non-academic as well) material for the memorandum I have to prepare for

(somebody’s) the Justice William Brennan Liberty and National Security Project

(where I interned back when I wrote this a few years ago), I was struck by two things: (1) the number, scope and depth of legal articles that had been written on the most specific issues involving the prosecution of suspected terrorists and (2) that none of what I saw (at least those that were electronically accessible through (some American law school’s) excellent library and links to academic journals and publications) had been written by writers who might be located in developing countries where terrorism is part of daily life, with its violence and the impact of such violence on immediately-affected communities.

"Was this merely because the

(American law school’s) New York University Law School's technological reach (as well as that of the commercial electronic libraries that it allowed access to) deliberately did not cover or include material published in some countries, universities or law schools abroad? Or was it because there are no such materials?

"If it were the first, then it would be a significant inadequacy: American lawyers, and especially American human rights lawyers deeply engaged in policy advocacy, would gain much from the views and insights of lawyers (including human rights lawyers, legal academics and social scientists) from developing countries on law and terrorism. Whatever material on law and terrorism – whether lengthy law-journal articles or simple comments in publicly-available magazines (in print or in electronic form) – that comes from these developing-country legal sources may be insightful, given the presumed proximity of the writers to what is, literally, the battlefield in which “terrorism” (or militancy or whatever euphemism might be more appropriate) is spawned or fought. As it is, among American lawyers involved in the debates over legal issues arising from the U.S. Government’s conduct of its “war on terror” (and here I recall (a professor’s) reference to

Jon Stewart’s humor, because I recall what Stewart once wrote about the ‘war on terror’ – where he

asks why the common noun is now being used: is the US at war even against roller-coaster rides and its terrorizing effects?), the lines have been drawn and drawn so clearly that I now understand, in a way, what the (Liberty and National Security Project I'm working on)lawyers may have meant by their reference to “neutrality” in some areas of that debate. Whatever one’s side of that debate, it seems to be a debate predominantly engaged in by and within

American and

European academic and legal circles, a debate that concerns how the world might be shaped by this ‘war on terror’ yet without (seemingly) hearing any voice from among those who might represent not one of either side, but another perspective from another part of the world that might give a different context altogether to the issue.

"Not much, for instance, has been said about the impact of the ‘war on terrorism’ on overseas workers from the

Philippines,

Sri Lanka,

Indonesia or

Bangladesh who continue to work in the Middle East, including in Iraq and Israel. Would the

UN Migrant Workers treaty have any relevance in this largely intra-Western debate about the legality of everybody’s conduct in this ‘war’? Nor has much (as far as I can see) been heard about the legal issues surrounding the presence of American troops in the southern Philippines region or of the shifts in orientation of American military exercises in Southeast Asia since the ‘war on terror’ began. Everything, as (my law professor) noted, is “post 9/11.” Even massive deaths by tsunami are blithely

compared to how Americans reacted to the numbers killed by terrorism on that apparently, for some, more significant day.

"On the other hand, it could simply be that not many in the developing world have taken the time and effort to write briefs, memos and articles about the legal impact on their people of this war. I hazard the view that writing about law and terror might be a luxury not easily affordable to law professors in poor developing country universities where tenure doesn’t mean anything more than being paid above the minimum wage and “publication,” while required, means printing a few hundred copies of a journal that will come out two years later. Human rights lawyers in NGOs of developing countries who might find time to pause from trying to convince foreign donors that there are other equally urgent concerns needing funding than what the donors think should be funded, may still not find a reason to ponder the meaning of law in a time of a ‘war on terrorism,’ if the life-and-death issues faced by the rural communities they try to serve are really the same life-and-death issues faced by their clients even in times of so-called peace.

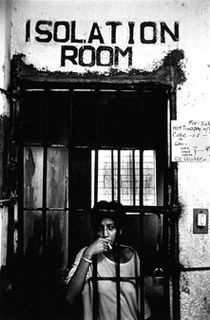

"Still, there must be some view of, for example, some Muslim lawyer trying to free

innocent Muslim boys in a Zamboanga detention cell from the prejudices of corrupt policemen emboldened by the distant encouragement they have been getting from no less than the President of America. I found

one such link, happily, and I am still hoping to see more of these views as I move forward. Still, I realize that one casualty of the ‘war on terrorism’ is the disproportion with which the world (or perhaps the Western world and the Western media) sees the adverse human rights impact of the U.S. Government’s conduct:

Guantanamo and

Abu Ghraib become monstrosities that require all the energies of the forces of liberty to counter, while the fate of unnamed children who live and die in the jungles of Basilan, labeled terrorists but really just barefoot, hungry and with nowhere to go, are footnotes in the history of humanity’s conflicts. My intellect sees the importance of defending the rights of

American citizens who volunteered to fight with the Taliban; but I wonder what the world can do for desperate peasant boys who would easily answer the call of a god that tells them to kill because they would otherwise die of hunger anyway?

"These are thoughts that will not make it to a law journal article and I suppose that may really be one reason why we don’t find much of this on what, supposedly, is the world-wide web.

Imelda's future suite

Imelda's future suite Coming soon?

Coming soon?