A corrupt judge + a corrupt litigant =

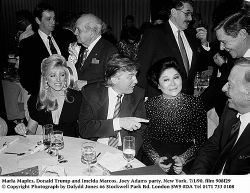

The Tramp with the Trump, back when she didn't have to bribe anyone so she could travel using stolen money.

If the Supreme Court ultimately lets this absolutely corrupt judge get away, I am going to be a very, very unhappy boy. Here's why:

The judge: Oscar Barrientos

The court: The Regional Trial Court of Manila

The case: Twenty-three (23) criminal charges of dollar-salting -- what we now call money-laundering -- committed by Imelda Marcos with the late Roberto Benedicto and his subordinates back when her husband was still - ahem! -- a living thief and dictator.

(Now, he's just a dead thief and dictator -- which Imelda claims isn't only untrue but is a libelous statement to make! "So, sue me," somebody said. That Imelda did.

(Then, proving that the Honorable Judge Barrientos isn't going to be the first and last officer of the court that ill-gotten wealth can buy, guess who decided that, yes, there is libel in there because, just maybe, history never happened and Marcos may not have been a thief and a dictator after all? "Baboons," someone called them. But that might be giving them too much credit. But back to our Judge Barrientos story... )

The issue: Imelda wanted to, as usual, travel. Her lawyers filed a "Motion for Leave to Travel" indicating that their peripatetic client wanted to go to (1) Lourdes in France (perhaps to cleanse her sins) and (2) Rome in Italy (perhaps to resume her sinning).

The judge granted the motion...but

The corrupt act: His order of approval went beyond what Imelda's motion asked for. He allowed Imelda to go to Lourdes, then to Rome -- and to London! Even if Imelda never said she was going to London? Yes.

More corruption: Realizing how embarrasingly obvious it was that someone must have been paid by somebody so that Imelda's last-minute travel plans could be inserted into that court order of approval, the Honorable Judge Barrientos went from bad to worse. He met right inside his office with a lawyer of Imelda; after the necessary whispers were exchanged (along with anything else that may have been sought or promised or bought and sold) -- presto! -- the Marcos lawyers had a new afterthought of a motion: "Yes, thank you Judge, our client really wanted to go to London, too!" The happy corrupt litigant.

The happy corrupt litigant.

(One of those lawyers, according to this link, has been placed under investigation by the Supreme Court.)

The grievance: The PCGG and the DOJ went to the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals, respectively. The PCGG sought disciplinary action against the judge. The DOJ sought his inhibition. The Supreme Court (apparently) simply sustained the Court of Appeals' ruling directing the judge's inhibition. So now he's out of the case. But...

(Read this link for more about what what this judge did and what should have been done to him.)

My problem:Is that it? Would that even qualify as a slap on the wrist? The Honorable Judge wasn't just acting as Imelda's over-eager travel agent. Here was a judge who went out of his way to defeat the good reasons behind the rule that seeks to prevent plunderers from simply buying a first-class plane ticket abroad, to where they can count and spend their loot.

The Supreme Court has removed ordinary court employees for failing to do their work or for just being absent. They even dismissed a court interpreter for -- of all things -- having an affair with a married policeman! Now, here's a judge who actually worked -- for Imelda. He was ever-present -- to do her bidding. And what did the Court Administrator recommend the Supreme Court should do to Judge Barrientos? Nothing. Nada. If the Supreme Court wants to send the message of zero-tolerance for corruption in the judiciary, then here's your boy. Kick him out. In fact, charge him with a crime under Article 206 of the Revised Penal Code.

I am so unhappy that the Supreme Court missed this chance to kick out a corrupt judge. How about you? If you are, too, here are the persons you can contact:

Send email to the Supreme Court's Public Information Office.

Or better yet, make a phone call to the Office of the Court Administrator at telephone numbers (632) 523-7385 or (632) 525-1238.

(Now, that was a nice, relieving rant.)